24.03.2025

24.03.2025

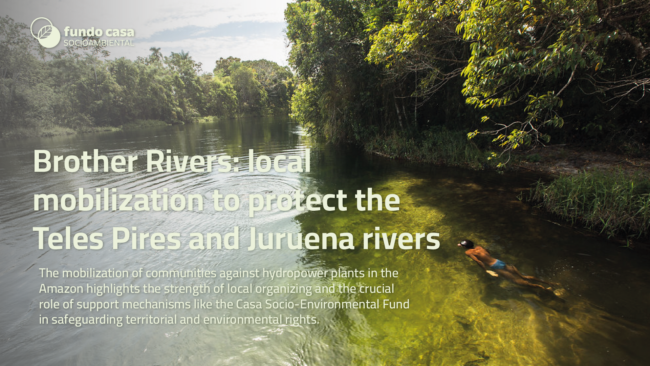

Brother Rivers: Local Mobilization to Protect the Teles Pires and Juruena Rivers

The mobilization of communities against hydropower plants in the Amazon highlights the strength of local organizing and the crucial role of support mechanisms like the Casa Socio-Environmental Fund in safeguarding territorial and environmental rights.

For many Indigenous peoples, rivers are sacred — true spiritual entities that carry the history of their ancestors. They are sources of water, food, and transportation, essential to the survival of riverine communities and countless species.

For ecosystems, rivers are as vital as the forests that surround them. A living river must be free-flowing, allowing fish and other animals to migrate and maintain ecological balance. When dammed, a river loses part of its vitality, disrupting natural cycles — such as those of migratory fish species, which can no longer swim upstream to reproduce in suitable areas.

The Teles Pires and Juruena rivers play a key role in the Amazon’s hydrological network, joining together to form the Tapajós River, one of the main tributaries of the Amazon River. The Juruena originates in the state of Mato Grosso and flows along the border with Amazonas, while the Teles Pires also rises in Mato Grosso and flows northward, marking the border with Pará until it meets the Juruena.

This river basin crosses two essential biomes: the Cerrado and the Amazon, forming a transition zone rich in biodiversity. Over 20 Indigenous peoples live in this region, alongside riverine communities, fisherfolk, and forest-dwelling populations who depend directly on the rivers for food, transportation, and the preservation of their culture.

Aerial view of the Juruena River shortly before it meets the Teles Pires River to form the Tapajós. This region is considered the last large block of native Amazon rainforest in the state of Mato Grosso. Photo: Thiago Foresti

However, this abundance also attracts threats. The Teles Pires Complex, one of the largest hydroelectric projects in the Amazon, includes six dams across the states of Mato Grosso and Pará. The project has been widely criticized by Indigenous communities, riverine populations, and socio-environmental organizations due to its regional impacts — such as changes to river flow, a decline in fish populations, and disruptions to traditional livelihoods and ways of life.

Although hydropower is often considered “green and clean” for producing fewer greenhouse gas emissions, dams still cause severe environmental harm, especially in complex biomes like the Amazon.

“Hydroelectric dams affect all life around them. The river is the essence of life — from the food it provides to how communities move around,” says Jefferson Nascimento, coordinator of the Movement of People Affected by Dams in Mato Grosso (MAB-MT). For Indigenous peoples, rivers are deeply tied to their cultural and social reproduction.

Uncatalogued rock inscriptions near the São Simão Waterfall on the Juruena River. Photo: Thiago Foresti

In addition to altering the water’s course, dams flood sacred sites of Indigenous peoples such as the Munduruku, and they accelerate the release of methane gas, intensifying environmental impacts. The problem is compounded when vegetation is not removed before flooding, which speeds up the decomposition of organic matter.

Aerial view of the area flooded by the Sinop Hydroelectric Plant. When vegetation clearing is not properly done, the forest is drowned and dies, releasing greenhouse gases like methane. Photo: MAB-MT Archive

Since the project’s inception, the Teles Pires Forum has mobilized communities to demand rights and compensation. This struggle has led to legal actions, public hearings, and international complaints about rights violations. Strategies like participatory monitoring, leadership training, and community exchanges have strengthened organizing efforts to defend the rivers.

Salto Augusto waterfall on the Juruena River in Apiacás (MT). With a drop of around 20 meters, this waterfall is listed in the ten-year plan of the Energy Research Company (EPE) as a potential site for generating 1.4 GW of energy. Photo: Thiago Foresti

Despite the progress, communities still face a lack of transparency and difficulties in accessing rights. The resistance around the Teles Pires River has become a symbol of the fight against new hydropower projects in the Amazon, influencing the defense of other rivers, such as the Juruena, where similar projects were blocked.

At the end of 2024, communities succeed in removing the Castanheira Hydroelectric Plant from Brazil’s national energy plan — and keep mobilizing

After nearly a decade of mobilization and joint efforts from various organizations, the Castanheira Hydroelectric Plant (UHE Castanheira), planned for construction on the Arinos River — a tributary of the Juruena, in Mato Grosso — was officially removed from the 2025–2034 Ten-Year Energy Expansion Plan (PDE). The decision marked a major victory for Indigenous peoples, rural communities, and socio-environmental organizations that stood in defense of the river and its surrounding territory against the social, environmental, and cultural damage the project would have caused.

The Castanheira HPP would have been built on the Arinos River, one of the tributaries of the Juruena. Photo: MAB-MT Archive

Jefferson Nascimento, coordinator of the Movement of People Affected by Dams (MAB-MT), emphasized the significance of this win: “The removal of the project is a result of the struggle of the communities and organizations. Otherwise, this dam would already be in operation,” he said. Since 2015, local communities and Indigenous peoples have organized in resistance, voicing concerns over the environmental and social impacts of the proposed dam.

He also pointed out that while hydroelectric projects are often framed as solutions to local infrastructure shortages — such as lack of jobs or public services — the actual outcomes, as seen with the Sinop HPP, have been marked by environmental destruction and violations: “These projects promise progress, but what we’ve seen is devastation,” he explained.

Through the mobilization of the Juruena Vivo Network, supported by various organizations and Indigenous groups, a technical and legal dossier was submitted to Brazil’s Ministry of Mines and Energy (MME), challenging the project’s feasibility. In 2023, the environmental licensing process was officially shelved by the Mato Grosso State Secretariat for the Environment (SEMA).

“This mobilization was only possible thanks to ongoing support from partners like the Casa Socio-Environmental Fund,” said Jefferson, highlighting the importance of logistical support in a region that is difficult to access.

Action carried out in the Tatuí Village, within the Apiaká-Kayabi Indigenous Territory, Mato Grosso. The territory is crossed by the Rio dos Peixes, an important tributary of the Juruena River that could face severe impacts from dam construction, directly threatening the traditional way of life of Indigenous communities. Photo: MAB-MT Archive

Despite this victory, Jefferson warns of ongoing threats. The Juruena River Basin remains under pressure from around 180 hydroelectric projects, most of them small-scale. “Our focus now is to monitor these smaller projects which, when combined, have major cumulative impacts. The struggle continues,” he said.

Silvio Roberto, also a coordinator at MAB-MT, reinforced the importance of grassroots mobilization: “MAB works to ensure these projects are not built, because we know they don’t solve the real problems faced by communities. Often, they’re designed to benefit large investors,” he said, citing the example of the Teles Pires dams, financed with foreign capital.

Silvio also emphasized that, given the prospect of more than 180 hydro projects planned in the Juruena basin, the Juruena Vivo Network had to broaden its strategy. “There’s no point in defending just one stretch of the river — the projects would simply shift elsewhere. Our main goal was always to stop the Castanheira HPP,” he concluded, stressing the importance of exchanges with communities affected by other large projects, such as Belo Monte, to strengthen the resistance movement.

The fight against dams and the defense of traditional territories

Representatives of the Kayabi, Apiaká, Munduruku, and Rikbaktsa peoples gathered in 2015 in the Teles Pires village to discuss the impacts of hydropower projects in the region. Photo: Attilio Zolin

The presence of Indigenous peoples such as the Kayabi, Apiaká, and Munduruku in the region predates Portuguese colonization and reflects a long-standing and complex network of exchanges and communication throughout the Tapajós Basin. However, over the centuries, these peoples have faced repeated violations of their rights, which intensified in the 1950s with government policies promoting agribusiness, mining, and logging.

In the 1980s, under Brazil’s military dictatorship, studies began for the construction of a hydroelectric complex in the region — raising alarm among traditional communities and environmental experts. The process gained momentum in the late 2000s and culminated in the creation of the Teles Pires Forum in 2010. This movement brought together unions, universities, community associations, and socio-environmental organizations to denounce the human rights violations and environmental impacts caused by the projects.

Impact caused by the construction of the Teles Pires Hydroelectric Plant in 2013. Photo: Thiago Foresti

Today, the Teles Pires is the Amazon river with the largest number of large hydroelectric plants in operation: Sinop, Colíder, Teles Pires, and São Manoel. The construction of these dams has led to the loss of territories, disruptions to local livelihoods, and serious socio-environmental impacts. Moreover, the implementation of the Teles Pires–Tapajós Waterway — designed to facilitate the transport of agribusiness commodities — continues to drive demand for new hydroelectric projects in the region.

Mobilization remains active. Since 2015, the Teles Pires Forum has been monitoring the impacts of the dams, producing reports, and organizing gatherings to strengthen affected communities. In 2022, the Movement of People Affected by Dams (MAB) and Indigenous associations intensified efforts to demand accountability from companies and push for reparations.

The dead forest left behind after the flooding caused by the dam constructions creates desolate landscapes. Photo: MAB-MT Archive

The struggle for the Teles Pires and Juruena rivers remains a symbol of the defense of Amazonian territories — with local communities, social movements, and support organizations working to develop sustainable alternatives and secure the rights of the peoples of the region.

Mobilization against the impacts of hydropower

The fight against the socio-environmental impacts of hydroelectric dams in the Teles Pires region has been marked by the intense mobilization of various groups — from social movements to university researchers. One of the early leaders in this process was João Andrade, a member of the Teles Pires Forum, who recalls the beginnings of the resistance and the challenges faced.

“It all started with a collective in the Teles Pires region — the Teles Pires Forum — which brought together universities, social movements, unions, and local communities. The group set out to understand and document the impacts that the dams would bring to the population,” explains João Andrade.

Researchers and members of the Teles Pires Forum during an expedition in 2015. The vast distances of the Amazon, often requiring hours or even days of travel to reach communities, make the logistics of any activity extremely costly. Photo: Attilio Zolin

According to João Andrade, when the mobilization began, the dams were already in advanced planning and licensing stages, making resistance especially difficult. “It was trench warfare — each group defending its own territory: farmers, fishers, settlers. There was no real dialogue with the population before the government made its decisions,” he recalls.

The Movement of People Affected by Dams (MAB) was already active in the region and played a key role in grassroots organizing and educating communities about environmental licensing processes and impact mitigation programs. The strategies included in-depth studies on the projects, political advocacy, and the production of audiovisual materials to raise public awareness about the consequences of dam construction.

Despite strong mobilization, João Andrade acknowledges that the process involved both difficulties and learning: “We arrived when the plants were already decided by the government and under construction. Resistance was essential, but perhaps we should have invested more in legal literacy and in building stronger legal strategies to defend the rights of affected communities,” he reflects.

Still, the resistance left a lasting impact and strengthened local organizations. “We brought movements together, supported Indigenous associations, and created networks that are still active today. That’s something you never lose,” João concludes.

Essential support and the role of the Casa Socio-Environmental Fund

The movement reached a turning point when it obtained financial support to strengthen the resistance. “We didn’t have any backing at first. It was with support from the Casa Fund that we were able to get out into the field, understand the situation, and organize a resistance strategy,” says João Andrade.

This support made it possible for technicians, researchers, and social movement representatives to visit affected communities and build a mobilization agenda. “It was a powerful moment for those involved. That first meeting was essential for organizing the defense of the rights of the affected communities,” João adds.

Indigenous community on the banks of the Teles Pires River, near the São Manoel Hydroelectric Plant. Photo: Attilio Zolin

Financial support for legal actions and environmental monitoring has been fundamental to strengthening community resistance to hydropower projects in the Tapajós Basin. According to Maíra Krenak, program manager at the Casa Socio-Environmental Fund, mobilizing local populations is essential for securing rights and protecting territories.

“The Casa Fund is committed to supporting communities in the defense of their territories and rights. This support enables strategic legal actions that help protect community rights and preserve environmental balance,” says Maíra. She emphasizes that the impacts of large dams go far beyond the physical construction — altering local social dynamics and disrupting all forms of life along blocked rivers.

The Casa Fund runs annual calls for proposals to support communities affected by mega energy projects, ensuring continuous support.

“We’ve been following the work of some of these organizations for nearly 20 years. It’s a long-term commitment to improving the living conditions of these communities,” highlights Maíra Krenak.

“Water for life, not for death” is one of the slogans of the Movement of People Affected by Dams. Photo: MAB-MT Archive

In recent years, organized resistance has led to important victories. For Maíra Krenak, “it’s incredible when a community succeeds in stopping the construction of a project of this scale in their territory.” For communities already impacted by such projects, the challenge is even greater.

“Once hydroelectric plants are built, they destabilize the entire territory, requiring much more complex interventions. That’s why continued support from funders is essential — so communities can restore balance, reactivate traditional healing systems, and regenerate their territories,” says Maíra Krenak.

Support for participatory environmental monitoring is one of the main tools for defending these populations. “It’s essential to engage the justice system to ensure contracts are honored and to continuously monitor environmental impacts, gathering evidence of rights violations,” explains Maíra. The Casa Fund and its partners remain committed to providing this support, ensuring that communities have the tools they need to resist and rebuild their ways of life.

Sunset on the banks of the Teles Pires River, at the Munduruku people’s Teles Pires village, in Pará. The community is located downstream of the hydroelectric complex and suffers from unstable water flow caused by the dams. Photo: Attilio Zolin

As activities expanded, new partnerships were secured, strengthening multiple fronts of action. “We created an activist communication front, which produced audiovisual materials showcasing community actions, such as Indigenous land occupations. We also established a monitoring front to track impacts and violations, which led to over a hundred civil lawsuits,” João Andrade explains.

The Casa Fund has supported strategic initiatives such as the “Monitoring and Advocacy Plan for Civil Society Engagement in the Licensing of HPPs on the Teles Pires River” and the “Socio-Environmental Impacts Observatory of Large-Scale Projects,” which promote coordination among Indigenous peoples, settlers, and fishers in the defense of their territories. Leadership training and advocacy campaigns have brought international attention to the impacts of hydropower, including at the World Hydropower Congress (WHC 2019) in Paris.

Since 2013, when it supported the Teles Pires Energy Observatory, the Casa Fund has strengthened resistance networks and amplified the voices of affected communities. With direct impact on dozens of leaders and indirect reach to thousands of people, these initiatives continue to raise awareness about the socio-environmental consequences of large dams and reinforce the fight for justice and territorial rights.

Mayrob Village of the Apiaká people, on the banks of the Rio dos Peixes in the Apiaká-Kayabi Indigenous Territory, Mato Grosso. Photo: MAB-MT Archive

The experiences along the Teles Pires and Juruena rivers demonstrate that popular mobilization — combined with legal, technical, and communication support — depends heavily on funders committed to socio-environmental justice. This support is essential for ensuring resources are available for territorial defense strategies and for preventing projects that threaten traditional ways of life.

As Silvio Roberto of MAB-MT notes, “Mobilization must be a way to unite communities, so they don’t remain isolated and can secure their rights.” That unity has proven essential for protecting territories and resisting projects that could cause irreversible harm to nature and people.

The defense of the Amazon’s rivers is a fight for the future. And every territory protected today strengthens the resistance against new threats — ensuring that forest peoples remain the primary guardians of biodiversity and environmental balance.